About the Retrospective Award

This text, by Pat Murphy, originally appeared in the WisCon 20 Souvenir Book.

The James Tiptree Jr. Memorial Award is now in its fifth year. Thanks to the efforts of bakers and bake-sale-organizers, cookbook writers and t-shirt makers, quilt-makers and writers, the award that began as a joke is going strong.

To celebrate our fifth anniversary, Karen Fowler and I, with all the authority vested in us as Founding Mothers of the Award, decided that it was time to put together a list of stories and novels that might have won the Tiptree Award, back before the Tiptree Award existed. We colluded in this endeavor with Debbie Notkin, the illustrious chair of the first Tiptree Award jury.

So here’s what we did. We contacted all the folks who had served on Tiptree juries over the years and we asked each person to nominate five works for a retrospective Tiptree Award. We got nominations-and along with the nominations we got complaints, questions, suggestions, and thoughtful letters.

Only five nominees?! Were we nuts?

“This is a difficult task,” Pamela Sargent wrote. “This list could easily be a couple of pages long.”

“You’ve asked me for five nominations for a Retrospective Tiptree Award,” Gwyneth Jones wrote. “I don’t know where to start.”

When she sent along her list, Nicola Griffith wrote, “There are at least half a dozen more I’d like to see up there.” They all were correct, of course, but our dutiful ex-jurors (even those who pointed out how unreasonable our request was) faithfully narrowed their selection to five.

Vonda McIntyre wrote, quite rightly, “This is kind of a no-brainer, isn’t it? The first retrospective Tiptree should go to Uncle Tip. If you have to have a title, “The Women Men Don’t See,” but better for the body of work.” Was James Tiptree eligible for the Retrospective Tiptree Award? That question hadn’t occurred to us. Alice Sheldon did, of course, write the definitive Tiptree-Award-winning stories (and, while doing it, lived a Tiptree-Award-winning life). Ultimately, we decided that the existence of the award itself was a tribute to James Tiptree and that giving Alice Sheldon the retrospective award would be redundant.

People struggled to determine what criteria they should use in making their choice. “I started to think of books that had meant something to me when I first read them; books that challenged my assumptions, delighted me with their irreverence, made a difference in my young life. It really highlighted for me how much the award is of its time. “Maybe we shouldn’t let people vote for things they weren’t old enough to read when they were printed!” suggested Ellen Kushner.

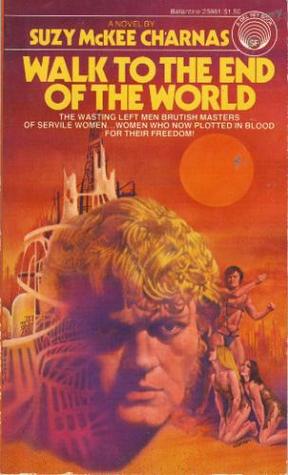

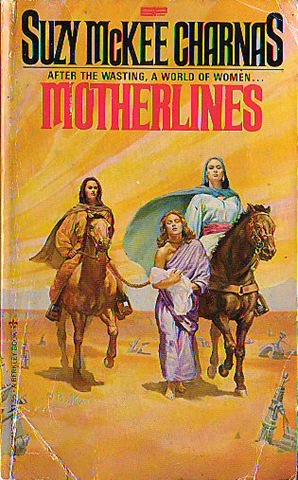

Having given people one difficult task, we compiled the nominations to create a ballot. We decided to combine some nominations, grouping Joanna Russ’s “When It Changed” with The Female Man, and grouping Suzy McKee Charnas’s Walk to the End of the World with Motherlines. In both cases, the works seemed irrevocably joined.

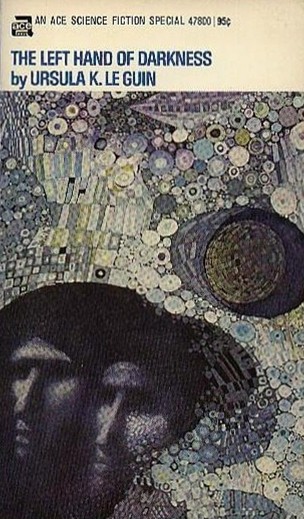

We then sent our former jurors a ballot with an even more unreasonable demand. We asked them to choose three works from the list of nominees. It was very very difficult. We know that. With their ballots, people sent notes describing the reasons for their selection. Some people chose to vote for classics in the field, works that forever altered the way gender is used in science fiction. Other jurors chose works that stood out, in memory, as their strongest personal encounters with the field. As Gwyneth Jones wrote of her selection, “These are not the three books I think ‘are the best’ in a general way. They’re my three closest encounters: the books that zapped me personally.” Works by three authors clearly emerged at the top of the list: Motherlines and Walk to the End of the World by Suzy McKee Charnas; The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. Le Guin; and “When It Changed” and The Female Man by Joanna Russ.

Many other works had substantial support among the jurors; there were many works that people wanted to select – if only we hadn’t arbitrarily limited their choice to three. That list follows, annotated with comments from jurors. As you’ll see it’s an idiosyncratic list, reflecting the varied tastes of our jurors.

For me, this list has already served its purpose. There are books on it that I missed when they came out – and a few that I’d never heard of! For me, this is a list of future pleasures – books to seek out and appreciate. But I’d also like to note that this is not the final, complete, never-to-be changed list of what could have won a Tiptree Award. Like the award itself, the list may change over the years. Who knows? Five years (and hundreds of chocolate chip cookies) from now, we could torture another list of jurors with unreasonable requests.

— Pat Murphy

Special Award Winner

The 1995 jury chose 5 works for the Otherwise Award Special Award.

Walk to the End of the World, The Holdfast Chronicles Book 1, by Suzy McKee Charnas (Ballantine, 1974)

Walk to the End of the World is a fine book, memorable from the first reading and deeper and more complex every time you come back to it. But what it’s about, in the final analysis, is what we already know-and that is how bad things really are, and how bad things can get. Motherlines, on the other hand, is a book that breaks new ground from start to finish, without a breather for author or reader. “New stories must be told in new ways,” indeed, and Suzy McKee Charnas knew that from the core of her being when she wrote that book. Perhaps there is no task harder for the writer steeped in the old story than telling the new one-letting us imagine that the new story can even begin to exist. — Debbie Notkin

This unflinching look at an unbearable future requires of its readers a strong stomach and a clear head. In the Holdfast, men rule and women-“fems”-are worse than chattel. But the word “patriarchy” doesn’t really apply, for these men have abolished fatherhood, believing that it caused the collapse of earlier male-dominated cultures. Generational conflict is institutionalized, with Juniors expected to support Seniors until age entitles them to Senior privileges. Charnas’s courageous exploration of gender roles is nowhere more apparent than in her depiction of the fem leaders, for whom the survival of the fems-and hence of humanity itself-is the only imperative. Readers willing to follow her example will find themselves sympathizing with some unlikely characters and acknowledging that, yes, in certain circumstances, some appalling choices may be justified. — Susanna J. Sturgis

Work Information

Title: Walk to the End of the WorldAuthor: Suzy McKee CharnasSeries:

Series Title: The Holdfast ChroniclesSeries Number: 1Publisher:

Publisher Name: BallantineCountry: USYear: 1974Motherlines, The Holdfast Chronicles Book 2, by Suzy McKee Charnas (Berkley-Putnam, 1978)

In Motherlines, her sequel to Walk to the End of the World, Charnas faces head-on the question ducked by most revolutionaries and social visionaries: what about the baggage that all of us raised in imperfect times will almost certainly carry into the halcyon future? The Riding Women of the Motherlines tribes are unscarred by oppression; the Free Fems are shaped by their horrific experiences as slaves. Alldera the runner is claimed by both groups and at home with neither. Those who criticized Motherlines for having no men in it were wrong: not only are men firmly embedded in the memories of the Free Fems, they enter the Riding Women’s councils as the enemy beyond the horizon. Charnas broke new ground with this one. Sixteen years later, only a few have dared follow in her footsteps. — Susanna J. Sturgis

Work Information

Title: MotherlinesAuthor: Suzy McKee CharnasSeries:

Series Title: The Holdfast ChroniclesSeries Number: 2Publisher:

Publisher Name: Berkley-PutnamCountry: USYear: 1978The Left Hand of Darkness, Hainish Cycle Book 6, by Ursula K. Le Guin (Walker & Co., 1969)

The Left Hand of Darkness was for me, as I think it was for so many readers my age, my first time. In all the science fiction I had read before that, I had only found hints, tantalizing glimpses, of what I knew could be there. The Left Hand of Darkness threw open wide the doors that had been left alluringly ajar and said, “Come in. There’s more room here than you ever imagined. Let me show you what some of it is like.” — Debbie Notkin

By itself, this classic’s premise guarantees it a high place in gender-expanding literature. What if a people were all the same gender, and what if sex dominated them wholly for a few days each month and were a non-issue the rest of the time? Le Guin offers two distinct, complex societies based on this premise and hints at several more. But it’s a mistake to forget that played out against this backdrop is a moving, unconventional love story in which sex plays almost no part. Mile by hard-won mile, two humans separated by language, customs, and physiology create a partnership as profound as any marriage. But neither love nor change comes cheap: there is indeed blood in the mortar that holds the keystone. — Susanna Sturgis

Work Information

Title: The Left Hand of DarknessAuthor: Ursula K. Le GuinSeries:

Series Title: Hainish CycleSeries Number: 6Publisher:

Publisher Name: Walker & Co.Country: USYear: 1969When It Changed by Joanna Russ (Doubleday, 1972)

Also collected in We Who Are About To, The Zanzibar Cat and The Best of the Nebulas (ed. Ben Bova, Tor, 1989)

Work Information

Title: When It ChangedAuthor: Joanna RussCollection:

Title: Again, Dangerous Visions Editor: Harlan EllisonPublisher:

Publisher Name: DoubledayCountry: USYear: 1972The Female Man by Joanna Russ (Bantam, 1975)

A male friend of mine described The Female Man, around the time of its publication as “articulate rage.” The phrase has always stayed with me. We were all enraged, and few of us knew enough about it to give voice, let alone words, to our fury. Joanna Russ did that for us all. “When It Changed,” on the other hand, will always be a joyful story for me. Though much of the meat of the story is not joyful at all, that first sentence, sending Katy driving like a maniac over the roads of Whileaway, transported me to a place I knew I was glad to be, even as a visitor. — Debbie Notkin

“Anyone who lives in two worlds,” says Vittoria, Janet’s wife, “is bound to have a complicated life.” Joanna Russ’s quartet of Js live in four: Jeannine in a United States where World War II never happened, Joanna in a 1975 recognizable to any woman who lived through it, Jael in a near future where Manland and Womanland fight a desultory war, and Janet on Whileaway. Whileaway! A future world of self-sufficient women, where men are long forgotten. The Female Man is a dead-on hilarious tour de force; it doesn’t just explore gender roles-it explodes them. And is it dated? Not on your life! — Susanna J. Sturgis

Every time I reread “When It Changed,” the story amazes me all over again. It’s so short-just a few pages-and in those pages it takes a science fiction cliché and changes it forever. Since the days of the pulps, men have been rushing in (often with blasters) to rescue women. The assumption was, of course, that the women needed and wanted to be rescued. “When It Changed” shook that assumption-and many other assumptions-and left the science fiction field a more interesting place to live and write. — Pat Murphy