To be a Filipina is to be heir to histories of war and armed occupation over hundreds of years, and a present day born out of structural patterns of poverty and impunity. To be a Filipina is to be part of a siblinghood that includes Gabriela Silang as well as Tandang Sora, the call center worker attending rallies on no sleep as well as the magsasaka hiding from enemy soldiers under bales of grain. To be a Filipina is to resist, for all that life is a series of cages: the suffering martyr, the sacrificing mother, the family’s savior; the tireless worker, the giver without limit or flaw, the saintly Madonna, the weeping Magdalene; the source of everything and possessor of nothing; the one who exchanges her human dignity for her children’s chance at a future; the sex object, the white man’s idea of the perfect blend of “Eastern submissiveness” and “Western curiosity”. To be Filipina is to face that choice: be swallowed up by the weight of your past and the chaos of your present — or become a monster, and devour that which would devour you.

To be Filipina is to fight. To be Filipina is to hold beauty in one hand and terror in the other. To be Filipina is to be monstrous. To be monstrous is to be free.

My work arises from these stories. I view the monstrosity of the Other as something to reclaim and thereby defy everything that would speak of different as lesser. I view the monstrosity ascribed to Filipinas — from the time of the colonizers to those who would own us in the present day — as the unacceptable and frightening nature of women whose desires and hungers and fires have long been suppressed, vilified, denied. This is not merely monstrosity as beauty, as power; this is the monstrous because it cannot be neatly labeled and measured; because it remains unknown. This is reclamation of things that the West does not understand and thereby rejects. In this sense to be monstrous is to claim existence outside what can be seen and comprehended by the West. This is monstrosity as kalayaan; freedom and breaking out of oppressive power structures and validities of existence.

This is the work my Tiptree Fellowship supports.

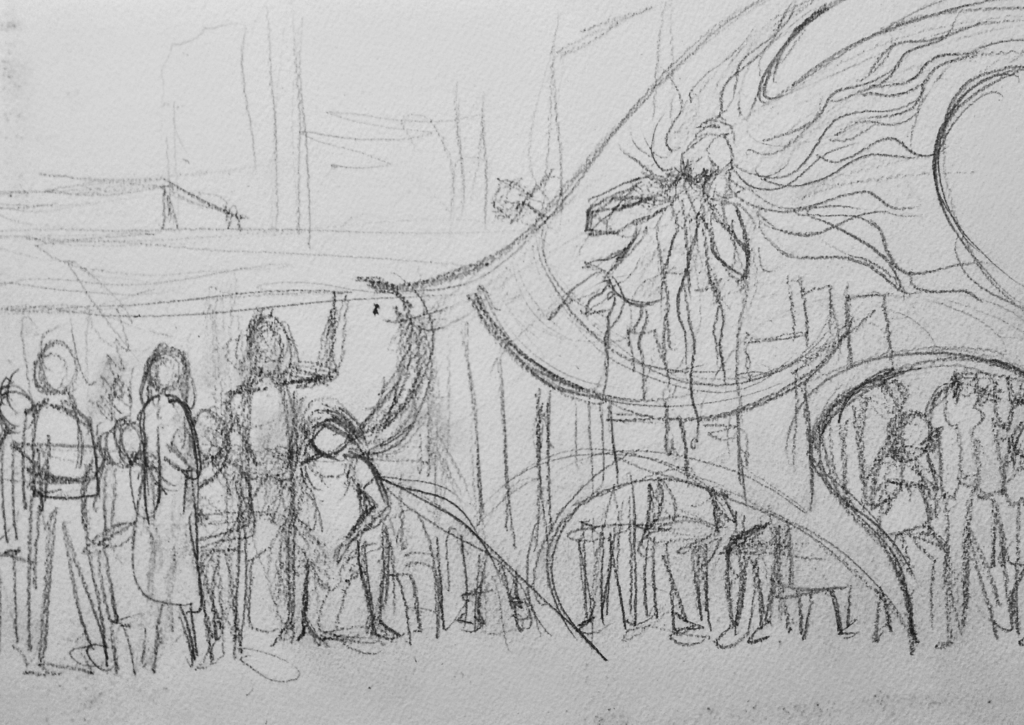

I cannot separate my being Filipino, of the Philippines, from my being a woman; they are inextricably intertwined. Thanks to the Tiptree Fellowship I was able to examine this intertwining more closely through my art. Life has not been easy this past year and between trying to keep my household afloat and taking care of my own health, I’ve had less time than I would have liked to work on my art series built around the concept of Filipinas as monsters, monstrosity reclaimed and embraced. Still, I’d like to share with you some work-in-progress pencils and concept sketches featuring both high fantasy settings and the supernatural as the second skin of our everyday.

What does the Tiptree Fellowship mean to someone who has feared, especially when she still lived in her country — a place scorned and exploited by the same imperialist powers that played such a part in its poverty; butt of jokes about our overseas foreign workers, our food, our values — that her work would never be acknowledged or valued in her own city, much less at an international level? It means immensely much. It’s transformative, in a very real sense, because it changes one’s fundamental belief about what one’s work can do and where it can go.

It means to be seen. It means to be affirmed when one says, I have a right to be here, and to be wholly and unashamedly what I am.

As I continue my work on my art series I find that even more than the monetary help from the Tiptree Fellowship, it is this being-seen that has been vital. I hope to share with you all my art upon its completion, to show you my vision of the faces of my monsters, my kapatid, and my self.