The Otherwise Award is pleased to announce that the award ceremony for the 1996 Otherwise Award winner(s) has been held, and the winners have received their award and accolades.

Award Information

Conference Information

- Award Year: 1996

- Award Year Number: Year 6

- Conference: ICFA International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts 18

- Date: 30-03-1997

- Location: Fort Lauderdale, FL

Award Winners

The 1996 jury chose 2 works for the Otherwise Award.

This is a fuller and, for Tiptree purposes alone, more satisfying exploration of the marital customs on the planet O, set up in earlier Le Guin work. In some ways, the story suggests that every society’s sexual norms and taboos are arbitrary and this is an interesting idea to bring back to our own world. In other ways, the marriages on O seem, as opposed to arbitrary, more rational and reasonable than our own simple twosomes. In the end, even on the world of O, it is the twosomes who finally dominate the story, and that, too, is interesting to think about. Le Guin never falls an inch short of brilliance. — Karen Joy Fowler A lovely story and yet another of Le Guin’s thorough and heartfelt explorations of new configurations of desire and belonging, both on a personal and a cultural level. — Richard Kadrey On rereading this story I was struck by its second paragraph, which says that mountain people “pride themselves on doing things the way they’ve always been done, but in fact they are a willful, stubborn lot who change the rules to suit themselves….” This story is partly about the gap between ideals and practice, and about the way that people make new traditions for themselves or change the old ones to fit their needs. The story takes place on the planet O (a place Le Guin has visited before), which has a system of marriage based on norms of bisexuality and polyfidelity. Le Guin portrays this culture with depth and subtlety, so that the story’s events and the characters’ development have a naturalness and inevitability. She’s also managed to create a story in which an act of cross-dressing has a whole different set of meanings than it would in our society. As usual, Le Guin’s sense of place is impeccable. — Janet M. Lafler A gentle, spare and beautiful story. Le Guin first introduced us to the marriage customs of O in “Another Story, or A Fisherman of the Inland Sea.” In that story the system of marriage was another detail of an alien world in a story centred around a time paradox. In “Mountain Ways” the implications and potential tragedies of these four-person marriages are explicated in exquisite detail. Like all fine science fiction and fantasy, particularly that of Le Guin, there is a double process at work; the alien is rendered knowable and familiar, and the taboos and normalities of our own worlds start to seem as “unnatural” as those within the story. Raising questions like why is marriage between two, and not three, four or five? Why is heterosexual union privileged over homosexual? Why formalise sexual relations at all? The story grew with each new reading so that many months after my initial reading I still find myself thinking about it and wondering about the deliberately ambiguous ending. One of my biggest pleasures in reading Le Guin’s work is its cumulative power and the way she takes up and reshapes elements of her vast invented universe so that you are forced to look at them in an entirely different way. — Justine Larbalestier The emotional effect of “Mountain Ways” is strengthened by its being about characters and relationships as well as about sexuality and morality. I like the way complexity of desire overwhelms the relative simplicity of the characters and the fact that no matter how flexible a social system seems, human beings can find new ways of making themselves feel guilty and sinful. As always with Le Guin, the writing is crystalline and the background much more lively and present than the number of words used to convey it would seem to warrant. — Delia Sherman Loved this novel–great old-fashioned science fiction in some indefinable way, but with a modern sensibility. A very smart and passionate book. I was initially concerned that the sexual content was slight, but my enthusiasm finally swept these doubts away. Although never quite defined as such, the transformation of the protagonist takes place largely through sexual experience, from his initial celibacy, to the middle of the book with his longings, to his final climactic and terrifying journey offworld. — Karen Joy Fowler A fine first contact novel and a subtle exploration of the choices people make in their lives, especially those concerning self-definition, which always includes sexuality and gender roles. — Richard Kadrey This novel haunted me for months; I kept thinking about it and mulling it over, and the more I did, the more I found to think about. The story centers on the spiritual crisis of Emilio Sandoz, a Jesuit priest who has had his view of God (and, not incidentally, his masculinity and his sexuality) challenged by his experiences on the planet Rakhat. The story of this crisis is counterbalanced by the stories of other priests, each with his own accommodation to sexuality and celibacy. On a different level, in her portrayal of the inhabitants of Rakhat, Russell makes fascinating connections among the binary oppositions of male/female, person/animal, ruling class/laboring class, pushing these connections in new directions. To say more about this would be to give away spoilers-and this book is so suspenseful that it wouldn’t be fair to do that. Suffice it to say that The Sparrow is rich and complex and provides a lot of food for thought about power, gender, sexuality, and the connection between body and spirit. — Janet M. Lafler The Sparrow is one of most haunting evocations of first contact I have read in recent years-on this occasion the contact is between a Jesuit-led team of scientists and some of the inhabitants of the planet Rakhat. How does the novel explore and expand gender? Central to The Sparrow is the examination of the importance of sexuality to gender identity, specifically masculinity. Can you be celibate and still be a man? At the same time the understandings of human masculinity and femininity that dominate the thinking of the Jesuit landing party make little sense in the face of the entirely different gender models of the two alien races. I read this not unduly small book in one sitting. I could not put the book down even though this Australian judge was somewhat put out by an entirely unconvincing (though mercifully brief) attempt at characterizing a ‘typical’ Aussie bloke (pp. 122-123). — Justine Larbalestier Profoundly moving and upsetting and very much about cultural constructions and difficult questions, including those of gender. Russell’s subjects are faith, religion, the structure and purpose of the Catholic Church (or maybe just the Society of Jesus), and saintliness. There’s a gay Father Superior and a woman who (although beautiful and petite) reads more male than many of the male characters. There is an alien race whose genders are ambiguous to humans, mostly because the females are larger than the males and the males raise the children. The center of the book is the hero’s struggle to reconcile the fact that the aliens he had moved heaven and earth to study have abused him terribly, with God’s Plan, celibacy, and his own macho upbringing. — Delia ShermanMountain Ways by Ursula K. Le Guin (, 1996)

Work Information

Title: Mountain WaysAuthor: Ursula K. Le GuinCollection:

Title: Asimov's Science Fiction August 1996Editor: Gardner DozoisThe Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell (Random House, 1996)

Work Information

Title: The SparrowAuthor: Mary Doria RussellPublisher:

Publisher Name: Random HouseCountry: USYear: 1996

Award Honor List

See full details about the 1996 Honor List

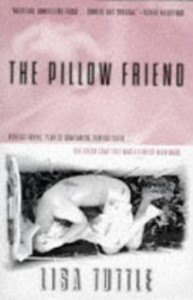

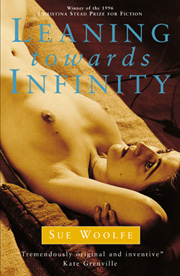

The 1996 jury chose 10 works for the Honor List “The Silent Woman” is not a short story, but a stand-alone chapter in the novel Farewell I’m Bound to Leave You. A wonderful exploration of “womanliness” which transforms the supposed passive virtue of silence into an almost magic strength. — Justine Larbalestier At the end of the millennium, noise is king. Flying in the face of that, this is a story that dares to explore the power and beauty of silence. And it does so beautifully, creating an exquisite object, like a literary Faberge egg. — Richard Kadrey In this gorgeous re-imagining of The Phantom of the Opera, Christine strikes a bargain with the Phantom and lives with him for five years. Much of the story has to do with the precarious balance of power between the two. Christine has a moral hold over the Phantom, but she doesn’t take it upon herself to absolve him, to reform him in any absolute sense, or to sacrifice herself to him. He remains a monster, and not always a sympathetic one. Their passion is based on this tension, and of course it’s one that can’t endure indefinitely, as Christine knows. The moral and psychological complexity of this story can’t be easily summarized. Think of it as an antidote to the fable of the evil man redeemed by the love of a good woman, but don’t stop there; it’s many other things as well. — Janet M. Lafler A fascinating exploration of domesticity and power and literary roles. Even though she’s the heroine of a Romance, Christine is no fainting, yielding, pliable victim. She is a hard-headed business woman who knows how to negotiate with managers and directors and monsters, too. Erik, on the other hand, is governed completely by his passions. In most Romances, the heroine must teach the hero to feel and to express his feelings. In “Beauty,” it’s the other way around. — Delia Sherman Thematically perfect for the Tiptree. I admired its brains and awareness of its subject matter immensely. It’s a wonderfully imagined externalization of all the little decisions we make every day that add up to who we will be as adults. Only in Duchamp’s world, the decisions are entirely self-conscious and deliberate and revolve around the gender role you will carry, like a big digitally-crafted, chrome albatross around your neck for the rest of your life. — Richard Kadrey In this story, an apparent gender freedom (the ability to choose one’s gender at a certain age) is embedded within a rigid gender system. A pointed commentary on the problem of “choice” when none of the options is worth choosing. — Janet M. Lafler In this “post-historical utopia,” which one of the characters describes as a “mild matriarchy,” women live in communal households and raise children, while most men live separately and pursue “manly” activities such as warfare. Sound familiar? That’s just the beginning. This is a funny, loony, and irreverent book, but it also has flashes of horror, despair, and lyricism, not to mention the best portrayal of warfare-as-sport that I’ve ever read. — Janet M. Lafler A story of heterosexual love as a sick compulsion. In this sharp, funny, clever story the disease undoes the very fabric of time and space. Straight men and women are aliens locked into combat until the end of time. Literally. — Justine Larbalestier The reductio ad absurdum of “can’t live with ’em, can’t live without ’em.” — Delia Sherman This is a book primarily about questions. As the protagonist comes of age at the opening of the western US, she begins to question everything in her world, including her identity and the settled life that she is expected to grow into. When she makes one crucial break with her past (avenging the killing of her parents), the questions deepen, encompassing everything, including her sexuality. What makes the book work is that the questions aren’t obvious and political in the soapbox sense, but grow out of the increasing natural awareness of a young woman moving into and finally rejecting the “civilized” world. — Richard Kadrey An exploration of (among other things) the borders between male and female, masculine and feminine. Nadya herself slides from man to woman as she slides from woman to wolf, redefining gender in the face of a society whose gender definitions are as unrelenting as they are arbitrary. The characters are persuasive, the background is colorful and beautifully researched, and there’s enough suspense and adventure to make it a convincing Western. A feminist Western. Well, that’s gender-bending, too. — Delia Sherman I thought the use of fairy-tale elements, while fun, was a bit easy and undisciplined. (Picture me with my arms folded and a stern look on my face. Undisciplined use of fairy-tale elements! Capital crime.) But I loved the identification of the fairytale godmother with death. If death seemed to be a little more the topic than sex, there was plenty of sexual stuff going on. It was a great read, with many beautiful moments. A top contender. — Karen Joy Fowler Pollack is interested in playing with types of fairy tale and contemporary society. In Pollack’s universe, the only real sin seems to be too strict adherence to one traditional gender. What I liked (and found Tiptreesque) about this book was the androgyny of many of the characters (especially the dead and inhuman ones). If the Le Guin is an exploration of Things as They Might Be, Godmother Night is an exploration of Things as They’re Getting to Be, with “gendered” behaviors like nurturing, passing judgment, avoiding intimacy, and wearing dresses seen more as a function of individual personality than of biological programming or social expectation. — Delia Sherman Not all horror novels have monsters and not all monsters have scales and wings. This is a novel about the horror of daily existence, of desire for an impossible “perfect” union. Where longing makes the whole world gray and seemingly constructed of chalk. — Richard Kadrey I had a visceral reaction to this novel-I loved it and simultaneously found it extremely disturbing. It captures perfectly one of the main reasons that people (particularly women) stay in bad relationships, ignore warning signs, and pretend to enjoy bad sex-because they’re stuck in their hopes and dreams from the beginning of the relationship, when they thought it was going to be the answer to all their desires. Thus, The Pillow Friend can be read as a story about the ways that both women and men are imprisoned by fantasies of romantic fulfillment; about the frustrated desire for perfect connection with another; and about the destructiveness of that desire. — Janet M. Lafler This story derives its impact from its position among other feminist texts to do with naming and unnaming (including the Biblical one). A young woman isolated on a remote planet creates her own words. A lovely variation on a favorite theme. — Karen Joy Fowler This story is rich with echoes of earlier science fiction by women. Like Suzette Haden Elgin’s fascinating Native Tongue trilogy, language is used to remake the world. However, this time it is one woman and her child who reinscribe the world in which they find themselves. The scenario of a young woman bringing up her child alone on a planet reminds me of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s 1959 story “The Wind People” though in Williams’ story the woman and her child reinvent their world rather than letting it invent them. — Justine Larbalestier This was one of my personal favorites among the books we read this year. Although it alludes to some fantastical mathematics, the fantasy content is minimal. It involves a family in which mathematical genius runs, unacknowledged and primarily untrained, through the female line. It deals with issues of women in (and out of) academia, of the appropriation of women’s work, and offers a quick education in the female mathematical tradition, sparse, but there. But the heart is a three-generational mother and daughter story. Beautifully written, absolutely original. Sensational! — Karen Joy Fowler I really loved this book. It’s about a famous mathematician, Frances Montrose, and is her history from the 1950s when she was a child until the discovery of her genius in the late 1990s. The novel centres around two first person narratives. The first I is that of Frances’ daughter, Hypatia Montrose, who is trying to come to terms with her extremely difficult relationship with her mother. The second is Frances’ I. However, the stories of this I are told as imagined by Hypatia. It is one of the most dazzlingly beautiful negotiations of the lives and relations of mothers and daughters that I have ever read. — Justine LarbalestierThe Silent Woman, Fred Chappell (St. Martin's Press, US, 1996)

Beauty and the Opéra or The Phanton Beast , Suzy McKee Charnas (Dell Magazines, US, 1996)

Welcome, Kid, to the Real World, L. Timmel Duchamp (Minnesota Science Fiction Society, US, 1996)

A History Maker, Alasdair Gray (Canongate Books, Scotland, 1994)

Five Fucks, Jonathan Lethem (Harcourt Brace, US, 1996)

Nadya, Pat Murphy (Tor, US, 1996)

Godmother Night, Rachel Pollack (St. Martin's Press, US, 1996)

The Pillow Friend, Lisa Tuttle (White Wolf Publishing, US, 1996)

And She Was the Word, Tess Williams (Eidolon Publications, Australia, 1996)

Leaning Towards Infinity, Sue Woolfe (Faber & Faber, Australia, 1996)

Award Long List

See full details about the 1996 Long List

The 1996 jury chose 37 works for the Long List

- Pussy, King of the Pirates, Kathy Acker (Grove Press, 1996)

This retelling of Treasure Island as “a girl’s story,” (the author’s words) is like Switchblade Sisters on the High Seas. A combination of high-theory on women’s bodies, possession and language and drive-in movie biker violence. There’s no one else who writes like Acker. — Richard Kadrey

- The Memory Palace, Gill Alderman (HarperCollins, 1996)

A wonderfully decadent and intricate look at traditional gender archetypes, ringing changes on celibacy, impotency, fecundity, purity, decadence, magic, story-telling, words, nature and unnature. Really well (if a touch over-) done. — Delia Sherman

-

The central character is engaging, the characters she’s made up of (you’ll understand that if you read it) are interesting, the book has a sense of humor about its subject (which takes some doing), and a sense of compassion about the things that living in an unrelentingly patriarchal culture do to men. — Delia Sherman

- Y Chromosome, Donald Antrim

Doug and his ninety-nine brothers have gathered in the family library for some male-bonding before dinner. A mighty funny look at the dance of dominance, told by a shoe-fetishist who ends up on the floor. — Karen Joy Fowler

Donald Antrim won a Macarthur Fellowship (“genius grant”) in 2013.

-

Whether or not this book is fantasy depends on your interpretation of a crucial scene towards the end of the book, though it certainly has minor fantastic elements (fortune-telling and premonitory dreams). So be warned: this book is only tenuously eligible for Tiptree consideration, but, in my opinion, too fine to be overlooked on a technicality. Alias Grace is a novel about the famous 19th century “murderess,” Grace Marks, a servant who was convicted, along with her fellow servant James McDermott, of the murder of their employer and his housekeeper (and mistress). The way in which the historical Grace was involved in the murders is not clear, and Atwood is careful not to give a definitive answer. Instead, through the imagined Grace’s experience, she explores work, sexual and class exploitation, fame, and the public fascination with murder, especially murder of or by a good-looking woman. Also innocence, responsibility, and memory. — Janet M. Lafler

-

Gender-exploring in a vein similar to that of Banks’ other Culture novels-the people of the Culture routinely change sex and many of the characters are genderless machine intelligences. In addition, one of the main characters in Excession is a woman who has arrested her pregnancy for forty years. Entertaining, but not Banks’ best work. — Janet M. Lafler

-

Block is a truly wonderful writer. Her power is rooted in a deceptively simple prose style which is compounded of young adult novels and children’s fairy tales. Block takes these simple elements and weaves magical little stories with them. “Blue” is the story of the breakdown (and resurrection) of a family after the mother’s suicide. The title character is a tiny transsexual dwarf who appears at a moment of crisis to a young girl in the story (and the only fantasy element). Is Blue an externalization of her own superego or simply a sign that she shares her mother’s madness? Will she survive to know? Unfortunately, there isn’t quite enough gender exploration in the story for it to be a Tiptree winner, but it’s as emotionally strong and true and well-crafted as anything the judges read this year. — Richard Kadrey

-

A creepy encounter between two teenage girls and Graves’ White Goddess, with an ambiguous end which may be interpreted as a critique of the patriarchal vision of the female muse. Or not. — Janet M. Lafler

- Dead Things, , Richard Calder (St. Martin's, 1996)

Dead Things is the resolution to a complex trilogy chronicling the coming of a new sort of being into the world: predatory and hyper-sexualized females, the Lilim. Imagine a kind of perfect, frictionless Barbie doll with fangs. Dead Things is all about gender, but its challenge is inverted. It doesn’t show new possibilities, but parodies accepted gender roles by pushing them to Wagnerian heights, making them all-defining, all-consuming and grotesque. It’s a brutal kind of parody-fascinating, but an acquired taste. And that’s part of the problem. Dead Things, the last book of the trilogy, does not stand alone. In fact, as the most stylized of the three books, it’s almost incomprehensible without the background and language provided by the other two books. Taken together, the trilogy–Dead Girls, Dead Boys, Dead Things–is a literary head kick, pushing gender and bio-tech buttons as hard as something like Neuromancer pushed the romance of digital criminality. My recommendation is to read the whole set of books. And maybe try to convince a publisher to reprint them in a single volume, or better yet, to publish something like this in a single year so that a future committee can consider the work as a single thing, rather than being served a wing and a leg and trying to vote on the whole chicken. — Richard Kadrey

- The Lucifer of Blue, Sherry Coldsmith (St. Martin's)

A haunting story of the Spanish Civil War. Coldsmith sets the piece in a brothel and gives us the amalgam of war and sex, without glamorizing or simplifying. — Karen Joy Fowler

- The Splendor and Misery of Bodies, of Cities (excerpt), Samuel R. Delany

An intriguing fragment in which the sexual identifiers change from paragraph to paragraph; woman appears to be the large category and man the subset, or the other. The setting is off world, there are aliens and the added layer of alien sexual identifiers. I am eager to see this play out in a longer work. — Karen Joy Fowler

This novel has never been published; only the fragment exists.

-

An exploration of the current status of the war between the sexes, The Big Chill with wings and talons. — Delia Sherman

- Distress, Greg Egan (Orion, 1995)

“Gender migration” as the ultimate critique of identity politics. Egan makes a credible case for the virtues of asexuality and androgyny, one that made me wonder just why I find the idea so disturbing. In contrast to Tepper, who comes off (to me at least) as anti-sex, Egan is clearly pro-freedom. — Janet M. Lafler

- Tiresias, Firecat (Circlet Press, 1995)

A very sexy story which, incidentally, illustrates the distinction between gender change and sex change. — Janet M. Lafler

- The Bones of Time, Kathy Goonan (Tor, 1996)

Great read. Reminded me of Distress a bit-a perilous, shoot-em-up mystery plot with a lot of physics theory filling in the cracks. Early on, the narrator, a Hawaiian woman of Japanese ancestry, mentions that the old gender-biased educational system has been completely eradicated. We then rocket through an international chase, which allows no time to pause and see what the results of this have been. But what we’re left with is a story in which no one’s sex seems to matter at all. Which has its own kind of refreshment for the weary reader. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

The adventures of Anita Blake, vampire assassin and zombie hunter. She’s a Christian and doesn’t believe in premarital sex. I find this more unusual and intriguing than the fact that she packs a piece and doesn’t hesitate to use it. Things have come to such a pass! For our purposes, there are interesting dominance issues throughout, made more interesting by the fact that half the characters are werewolves and pack animals. Lots of the book is same old/same old sexually, but enjoyed for the same old reasons, which means enjoyable. Great fun in fact. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

A very poetic book about two young sisters living in rural isolation after the collapse of civilization. None of the gender issues are very pointed, but the relationship of women and wilderness is a particular fascination of mine, and I found this an entirely engaging addition to the tradition. The writing is especially lush. — Karen Joy Fowler

- No Quarter, , Tanya Huff (DAW, 1996)

Tanya Huff has to be one of the most dependable writers of cracking good fantasies around. This book is no exception. Compulsively readable and great fun. The Tiptree elements concerns a man existing (as a separate being) within the body of a woman. However, for Tiptree purposes, there is really not enough exploration of this intriguing scenario. — Justine Larbalestier

-

A nasty twist on virtuality’s mutual dreaming and the insidious clichéd archetypes that have such a tenacious grip on our imaginations. — Justine Larbalestier

-

No one has ever managed to analyze the power of concubines in any new and interesting way. But in the last thirty pages of this wonderful book, Larsen does throw out our previous sexual assumptions and go somewhere unexpected. This is an intricate and beautiful book made up of stories about stories which contain stories, and I loved it. — Karen Joy Fowler

- The Reason for Not Going to the Ball (A Letter from Cinderella to Her Stepmother), Tanith Lee

A new version of an old nemesis. Lee’s fairytale shows that there is always and infinitely another side to things. A good addition to the growing body of Cinderella rewrites. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

A woman finds a man asleep on her doorstep and brings him into the house, where he remains asleep through various events. I read it as, in part, a comment on the lumpish husband who sits in front of the TV and is herded around by his wife: male protector/provider reduced to the role of passive icon. — Janet M. Lafler

-

A consciousness-raising novel about an old, working class woman named Ofelia who has spent most of her life bowing to the will of her husband, her employers, and her children. The book is mostly about Ofelia “finding” herself, developing a new strength, and, at the same time, becoming a pivotal person in the formation of the relationship between humans and another intelligent species. Elderly female protagonists are rare (I’m tempted to say unknown) in science fiction, and it’s refreshing to see one portrayed with complexity and honor. Unfortunately, Ofelia’s opponents and detractors are all straw men (and women); they are so completely one-dimensional and unsympathetic that Ofelia’s ultimate triumph seems cheapened. In retrospect, the most interesting aspect of the book, to me, was the aliens’ combination of youth (as a species) and intelligence. In science fiction, humans are often pitted against primitives or against older and more “advanced” (but stuffy and conservative) alien civilizations. It’s rare to see a situation in which humans are coping with a new, young alien race that’s smarter than we are. Of course, this has nothing to do with gender. At least, I don’t think so. — Janet M. Lafler

- Foragers, Charles Oberndorf (Bantam, 1996)

The set-up, with some agreeable twists and additions, is the human anthropologist among an alien race-known in this case as the slazans. Humanity is at war with one set of these aliens, when another, an isolated group of hunter/gatherers, is found. The human anthropologist finds among them that the primary value is for solitude. This is an ambitious book with an obvious sexual component and a complex web of plots and subplots. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

While not terribly pointed in terms of gender content, this novel does contain a marvelous send-up of beauty pageants and the American entertainment industry’s appetite for young murdered women. The protagonist is competing for the crown of Scream Queen and fighting her own unfortunate and unmarketable fearlessness. Very funny and absolutely original. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

The final and best book of one of my favourite science fiction trilogies of all time. On finishing it my first impulse was to go back and re-read the whole thing in one go. Robinson’s Mars is one of the most fully-realised, fascinating future histories ever written. However, from a Tiptree point of view, the book’s speculation about gender is disappointing. On page 43 we are told that sexual violence against women has disappeared and on page 345 that patriarchy has been brought to an end. We are not shown this reinscription of the roles of men and women, however, as, in much loving and convincing detail, Robinson delineates many of the other changes on Mars as its human society is created and grows. — Justine Larbalestier

-

A light-hearted story about the irrelevance of sex to gender, and vice versa. — Janet M. Lafler

- Fetish, Martha Soukup (St. Martin's Press, 1996)

I sometimes think that in the West gender difference is all about hair, not genitals-this story is a witty, sharp exploration of just that. — Justine Larbalestier

-

What Springer does with the structures and assumptions of fairy-tale, the way she weaves Story and psychology, the way she makes us hate a character like Prentis and then shows us enough of his vulnerability to make him more than a simple MCP stereotype-not to mention the fact that I kept laughing out loud-are delightful. — Delia Sherman

-

The protagonist is on anti-libidinals as a member of the Sexual Deliberation Movement, and argues briefly that true freedom is freedom from the urge to reproduce. There’s also a fabulous social worker in the story. All a bit peripheral, but fine stuff, nevertheless. — Karen Joy Fowler

-

It begins with a crone. In a period of extended lifespans, sex and family and connections of any kind are something she long ago put behind her. She is a well-behaved, rich, and powerful old person who says she has become something other than a woman. She takes a new rejuvenation treatment and becomes a young, beautiful, badly behaved girl and, for a time, a model. I don’t think Sterling understands the world of high fashion any better than I do, which is to say, not at all. The sexual aspects of his character’s identity are more interesting in the crone part of the book, which is relatively short, than they are in the vamp part of the book. And the sexual aspects are drowned under the less familiar and more fascinating generational aspects. What would it be like to be the last generation of humans who die? This is a wonderful novel and maybe Sterling’s best to date. — Karen Joy Fowler

- Clouds End, Sean Stewart (Ace, 1996)

A magical blending of fairy tale, myth and fantasy. Although the book is packed with as much fairy tale adventure as any Tolkien clone the book’s heart is in the realms of the domestic. The book offers a traditional hero named Seven and then makes his story a minor melody. Marriage, children and home are central. However, this is not the saccharine family values imagined by the political right. Home and hearth are as disturbing and uncertain as any of the more traditional sites of adventure Cloud’s End has to offer. — Justine Larbalestier

-

I wanted to like this book better than I did. It takes place in the near future, and it takes the form of a series of transcriptions of Internet communications with various backgrounds filled in through connecting narratives. It’s the story of two people’s erotic adventures on-line in a variety of different guises and genders, and of their battle against the world that doesn’t want to accept them. Perhaps inevitably, given its structure, it suffers from a certain “talkiness,” and I found the tone irritatingly self-congratulatory. — Janet M. Lafler

-

A scholarly mystery, all about history and research and women in Australia, told in Sussex’s best wry prose. Among its subjects are women’s roles on a frontier, communities of women, how men and women deal with women who act like men, and how men and women can be friends. — Delia Sherman

-

An intense disturbing story written in Swanwick’s usual elegant ice. You’ll never sleep with another dead person! — Karen Joy Fowler

-

This is a four-volume graphic fiction series.

Well drawn and well meant. The protagonist is a young girl, a homeless runaway, struggling to come to grips with her father’s sexual abuse. Three things eventually save her. They are 1) self-help books, 2) a move to the country-the countryside, itself, really-wilderness-and 3) her identification with Beatrix Potter. — Karen Joy Fowler

- Desmodus, Melanie Tem (Headline Feature, 1995)

Tem’s writing always disturbs me and Desmodus is no exception. She strips the vampire myth of any black nail polished romanticism. Her matriarchal vampires are wholly unlike any others, with lives which are on the whole nasty, brutish and sometimes even short. — Justine Larbalestier

Jurors

- Janet M. Lafler (chair)

- Karen Joy Fowler

- Richard Kadrey

- Justine Larbalestier

- Delia Sherman

Award Ceremony

See full details about the 1996 Ceremony

The 1996 Otherwise Award was given to Ursula K. Le Guin and Mary Doria Russell at ICFA International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts 20, March 30, 1997, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.