We’ve spent the last month deep in discussion about the name of this award. We’ve listened to your feedback, reflected on our own assumptions and commitments, and we have decided that it’s time for the name to change.

The Tiptree Award is becoming the Otherwise Award.

The rest of this long post describes our process in detail, shares some of the words from our community that helped us come to our decision, and explains why we’ve chosen Otherwise as our new name.

Use the navigation links below if you’d like to skip to a particular section.

The name of the Award: if you want to know why it’s changing

What we heard from you: if you want to understand how we came to this decision

What we’ve come to realize: if you want a short, snappy summary

What we feel: if you’d like to contemplate love, care, and tradition with us

So… the name? If you want to know how and why we chose Otherwise

What is not changing, and what happens next: if you’re curious about plans and timelines

A little help from our friends: if you want to support us through this transition

The name of the Award

When this award was founded back in 1991, its goal was to make the world listen to voices that had been ignored. Pat Murphy, cofounder of the Award and member of the Tiptree Motherboard, remembers, “We wanted to create an award that pointed out the absurdity of those who kept saying ‘but women can’t write science fiction.’ Naming the Award after James Tiptree, Jr. allowed us to celebrate Tiptree’s powerful writing and influence on the field — and at the same time, the name let us laugh at those who had dismissed women’s writing and yet had happily embraced Tiptree’s work as unquestionably masculine.”

In the beginning, the Award’s focus was on gender alone. Over the years, that focus expanded, but the Award’s goal is still to make the world listen to voices that they would rather ignore.

In mid-August 2019, in the wake of the Astounding Award’s decision to drop John W. Campbell’s name, the Tiptree Motherboard began to hear from some newly raised voices among our supporters. They were suggesting that the James Tiptree Jr Literary Award ought also to change its name. Since then, the seven of us on the Motherboard have been engaged in a deep, emotional, and intense process of discussion, introspection, and consultation.

On September 2, we published “Alice Sheldon and the name of the Tiptree Award.” That post summarizes the story of Alice and Huntington Sheldon’s deaths, and gives a full account of the events that led many to call for a name change. That story is deeply painful for many, we have realized, and we will not repeat it here. In our post, we explained why the Award’s founders named it after James Tiptree, Jr., and why, at that time, we were tentatively choosing to retain the name. In that post, we asked for you to email us with your suggestions. Many did. Thank you so much.

We received many emails and social media messages that urged us to keep the name. But we were, in the end, convinced by the many and heartfelt messages that asked us to change. We entered into this discussion as a conversation about how to interpret what happened at the end of Alice and Huntington Sheldon’s lives (a topic on which Sheldon’s biographer, Julie Phillips, has recently reflected further). But the responses to our post made us realize that this was in fact a conversation about whose lives and voices we value. And that’s a matter about which there should be no ambiguity.

We value the disabled writers and readers and artists and fans who support this award. Many of them – many of you – have told us that the Award’s current name holds negative, painful, exclusionary associations. So we’re changing it.

We know this has been a painful conversation for many. We are sorry we didn’t realize the depth of harm this would bring up.

Our decision to change the Award’s name has also caused pain. Many, even some who support the name change, feel that this change erases the work of an important woman author and the story of a complicatedly gendered life.

That’s a pain that we on the Motherboard share. The influence of Tiptree – the work published under the persona, Alice Sheldon’s life, and the history of this award – is important to the history of gender and feminism, as Julie Phillips’ 2006 biography and Rox Samer’s in-progress documentary film, Tip/Alli, document. Those of us who knew Tiptree as a man (either through letters or stories) remember the seismic shift we experienced when the identity of the person behind the persona was revealed. We will continue to honor that influence and to celebrate the feminist roots of our project. The Award’s name is not the only way to remember our important predecessors.

We do not see this new stage the Award is entering now as an erasure of its past, but as a recognition of what is needed to take us into the future. Pat Murphy and Karen Fowler came up with the idea for the Award, but they are the first to admit that they didn’t build the Award. A community built the Award and at the same time the Award built a community. Being part of that community has been serious work while being enormous fun.

We want the Award to keep encouraging writers, artists, and other creative people to invent the future that we want to live in. For that to happen, we need readers, supporters, and creators to gather together in support of the Award’s winners and of the process of choosing them. And for that to be possible, we need all the voices to be heard.

What we heard from you:

Some of the feedback we received suggested that the arguments for changing the name were coming from science fiction fandom’s right-wing trolls, keen to take down a social-justice-focused award as payback for the loss of the award honoring their icon John W. Campbell. We want to be very clear that this was not the source of the criticisms we received. The people who asked us to consider changing the name were people we know and trust: members of our community of supporters, with whom we have participated in feminist science fiction fandom for many years.

In this section of the post, we share some of the words from winners of the Tiptree Award and leaders within our community that helped us arrive at our decision. We encourage you to read them so that you can understand what has led us to believe that the name must change. We encourage everyone to read M.L. Clark’s beautiful essay “Letting Go of Our “Heroes”: Ongoing Humanist Training and the (Ex-)James Tiptree, Jr. Award.” Clark writes about their own process of thinking and feeling through the implications of the name change in a way that mirrors the experience of several members of the Motherboard during the last few weeks.

We appreciate how thoughtful people have been in their emails. In various ways, many have said: “The decision to change the Award name makes me very sad, but I understand why you have made this decision and I appreciate your willingness to share your process.”

It might have been possible to acknowledge the pain caused by the name and still continue to use it. Hirotaka Tobi, 2006 winner of the Japanese Sense of Gender Award – founded by the Japanese Association for Gender Fantasy and Science Fiction (G-Ken) and inspired by the Tiptree Award – urged us to do so in a letter generously translated by 2017 juror and G-Ken member Kazue Harada.

The name Tiptree has become a symbol of progress and inspiration in the literary field of science fiction.

I understand that you care about those who are hurt by the name of Tiptree, as your compassion and concerns have certainly been ‘cultivated’ by Tiptree’s works. Even though her end of life action has hurt many people’s feelings, even though there may be clues in her works that she was capable of the actions on her final day, I feel that her name cannot be dismissed. I strongly believe that the meaning of literature is to understand complex paradoxical meanings: on one hand, her works lean toward emphasizing the inevitability of death; on the other hand, these works give power to say ‘NO’ to death (suicide and murder) for readers. Our creative expression is developed and enriched through living with the pain of this paradox. I believe that you as a writer and as a scholar understand this paradox very well.

I would like to express my opinion that we should keep the name of the “Tiptree” Award, as we accept both her honor and disgrace demonstrated by her good deeds and horrible actions. In order to continue its name, I will suggest expanding the award to include nominated works recognizing new ideas of gender and sexual difference as well as authors broadcasting views of voices of those who have been suppressed because of illness and disability. I suggest grappling with not only the issues that James Tiptree Jr. was able to achieve but also the issues that she was “unable” to achieve. I propose that the award can develop into something for “those who have been killed by Tiptree.”

This award should bear the name of Tiptree in order to confirm this determination and to express its purpose. Every person is imperfect, but we seek to contemplate on our actions, hope to grow from the reflections, and live for atonement. As part of this process, the individual takes responsibility under one’s own name.

As we know, Tiptree is no longer with us. She is unable to pay for her own crime. However, we can discuss both her good and evil actions and can continue reconstructing the idea of the writer and award. We can continue developing the space for expressions of science fiction.

– Hirotaka Tobi, translated by Kazue Harada

Though this is not the path we have chosen, we include this excerpt to show our appreciation and respect for those who have thought through this issue deeply and reached different conclusions than ours.

The controversy over the name led Nisi Shawl, winner of the 2009 Award, to think deeply about her feelings about James Tiptree, Jr, and Alice Sheldon. She wrote this message for us to share:

I’ve been thinking about the controversy surrounding the James Tiptree, Jr. Award’s name ever since I first heard about said controversy, because I’m a disabled person who received the Tiptree in 2009. Also, I’ve served as a Tiptree Award juror twice, and served once as a juror for the related and similarly-named James Tiptree, Jr. Fellowship.

Looking back at my letter to Tiptree, written for the anthology of that title in 2015, I notice a couple of things. First, the conflation of those two figures, Tiptree and Sheldon. I addressed the letter to “Tip,” but I spoke of incidents in Sheldon’s life. I’m not alone in this conflation, though as the Tiptree Award Motherboard note in their carefully considered response to the controversy, the award is named not for the human being but for the trick she played on her audience.

The second thing I noticed is my wording toward the end of my letter describing the couple’s death. I’m not going to repeat it here, because taken out of context, what I wrote could cause you reading this post real pain. If you want to know the content of the two relevant sentences in my letter, contact me directly. What I’ll point out here is that my language in the letter was deliberately harsh. I wanted to scold Alice Sheldon, or “Tip,” as I addressed her, for her attitude and actions. I was assuming Ting’s acquiescence to his death, but mourning it, and decrying the emotional distance I believed it required from his killer. I referenced the dominant paradigm’s mistreatment of disabled people, but I was far from wanting to perpetuate its attitude. Yet that intention is not an antidote for the harm my words potentially could cause.

The issue of harm reduction in the naming of the award is the kind of multifaceted problem the award was founded to address–though the axis of difference on which it focused was originally gender rather than ability. And what I’ve been hearing and saying about how we respond to this problem? That is the kind of multiplex analysis the Tiptree Award’s founders were encouraging by naming it not after an historical figure but a mythic one, a mythic figure arising out of one writer’s response to powerful social pressures.

There’s still plenty to mull over here. And I’m fine with that. I’m also fine with having received the Tiptree. With having received an award named with that name.

But I don’t see how that makes it okay for me to say other potential recipients should think and feel the same way about the matter.

– Nisi Shawl

Nisi’s message offered some suggestions of ways that we might be able to continue using the name. But the responses we share below, among many others, convinced us that the change is necessary.

Elsa Sjunneson-Henry, editor and writer, wrote to ask us to change the Award’s name. The themes of her response, which connects the deeply personal to the collective and political, were shared by many of disabled creators and fans who wrote to us. We share this excerpt from her email with permission:

I am a deafblind Hugo award winning editor, and speculative fiction writer. My work focuses on the intersection of disability and media, as well as the intersection of disability and gender. I was the guest co-editor in chief of Disabled People Destroy Science Fiction, and I am writing to you today as a member of the science fiction and fantasy writing community, as a disabled activist, and as a writer.

First, I do believe that it is vital to change the name of the Tiptree Award. The intersection of disability and gender is an important subject, which I hope more authors will interact with. I myself write on that subject, and if I were lucky enough to be selected for the honor of the Tiptree (or its relevant lists), I could not in good faith accept it at this time. I believe many of my disabled peers could not either. The name of the award would feel antithetical to the work given the circumstances surrounding Sheldon’s murder of Huntington and her subsequent suicide. I don’t know what happened between Ting and Alice. I don’t know what their relationship was like – and based on what I’ve seen, I’m not sure anyone else does. That uncertainty means I could not fathom accepting an award named for an author who murdered someone like me. Perhaps an able bodied person could, but to me and my disabled existence it just isn’t possible.

Second, I hope that in consideration of a name change, the direction will go towards not naming it after a person. The world changes too much for legacies to remain, but ideals and constructs that do not represent persons are much more shelf stable. And we should interrogate legacies, we should try to be better.

Thirdly, I believe that the name change is important because ableism is a systemic disease. We can’t always see it, but it can be felt. It is felt deeply within our genre, and the conversation around the name of the Tiptree has only made it more clear to me: my professional field is rife with ableism, and we must seek to change that. Allowing the name to remain, with disabled people emphasizing their discomfort, implicitly allows ableism to take root. It allows us to say that disabled voices do not matter.

– Elsa Sjunneson-Henry

Among those who participated in the public conversation, two additional Award winners spoke up. Hiromi Goto, 2001 Award winner, 2001, posted this statement on Twitter:

I’m a recipient of the Tiptree award. … It behooves us to listen to & respect the experiences, concerns & corrections of the people who have systematically been & continue to be oppressed & marginalized.

My understanding is that some folks think that there was a suicide pact, others that there’s a grey area, others that it was murder-suicide. In this situation I would compare to the wording of how judges are selected for a competition. There’s that line of whether or not you have a bias or _a perceived bias_… And if so you should eliminate yourself from this jury. I think that there’s enough grey area to Sheldon’s history to outweigh the balance re: bias / perceived bias. Tiptree’s stories will always remain. They are powerful.

But with the passage of time and expansions in standpoint and we hear from voices who have never been centred we need the capacity, ability and love to be able to change. If the Tiptree Award is to honour fiction that expands or explores our ideas about gender then it would be a crying shame that the prize been perceived as one fixed in an ableist mentality.

I think it is time to #ChangeTheName I’m speaking with love and pride. I am proud to be a Tiptree Award winner. And I want to continue to be proud.

– Hiromi Goto

And Catherynne M. Valente, 2007 Award winner, posted this statement on Twitter:

If it matters, I won the Tiptree in 2007. I owe a great deal to this award. I’m trying hard to put my feelings about her work aside, as I ask others to do with regards to their heroes. She is gone & cannot be hurt, but those still here can. The name should be changed.

– Catherynne M. Valente

We saw our own decision process reflected in some emails, where people shared their own feelings about a name change. Debbie Notkin, the first chair of the Motherboard and the chair of the first Tiptree jury, wrote of the process she went through:

I cherish the Tiptree Award, and consider it one of the best endeavors I’ve ever been involved with…. In a vacuum, I would certainly argue for not changing the name of the award. All of our heroes have flaws—in fact, one of the worst aspects of having heroes is the desire that they be perfect. If we give into that, we can either have heroes or tell the truth, but not both. Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree, Jr. will always be a hero of mine.

But we are not in a vacuum. We’re in a community. And we’re in a historical moment when groups that have been horribly marginalized and abused are – often for the first time – finding that they can acknowledge their pain, make demands, make their voices heard, make change. And find allies….

I am trying to remember that it’s not only possible but common to be on many sides of a controversy at the same time. For me, the side that intensely wants to cling to the award’s name wants that because of all the history, all the sweat and tears, all the time and energy I and so many others poured into the Tiptree Award, not into some award that would someday change its name. That side also passionately cares about vindicating Pat and Karen for their courageous choices and all the world-changing that has gone on not just in Tiptree’s name, but in the name of the founding mothers.

The side of me that leans towards changing the name is about putting all my historical feelings onto a scale and weighing them against what the name is starting to mean to people who responded with their pain, and the knowledge that many more people aren’t responding because of their pain.

Debbie Notkin

What we’ve come to realize

The Tiptree Award was named as a joyful joke, 28 years ago.

James Tiptree, Jr/Alice Sheldon is a complicated figure who has grown more so as participants in the sff world have gained more diverse perspectives and more acute critical analyses. In 2019, the Tiptree name no longer captures what potential audiences, nominees, fans, need from an award (and, more recently, from a fellowship program) for the expansion and exploration of gender.

Some of the conversations surrounding this change, especially on social media, make it seem like a simple situation – a situation where you can say: “I am right and you are wrong. I will tell you the reasons you shouldn’t feel as you do, and you’ll stop feeling that way.”

But this is not a simple situation. It is, like life, difficult and messy and sometimes fraught with pain. But it is also, like life, brilliant and wonderful and filled with the possibility of joy.

Joy, absurdity, and irreverence have long been in the DNA of the Tiptree Award. What other award crowns the winner with a tiara, raises money with bake sales, and serenades the winner? Now, our community has spoken and said: there is too much discomfort over this history for many of us to feel joyous about this name.

Keeping the joy is more important than keeping the name.

We need a different name.

What we feel

In The Lathe of Heaven, Ursula K. Le Guin writes: “Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.”

This is love that we’re working with here. We love our award and the community that has grown from it.

And we love our supporters, and you love the Award too. And we want to reciprocate the hospitality you have shown us. Which involves not just logistical work, (figuratively) unlocking doors and setting up chairs and getting out food everyone can eat, but also the work of gesture, to emotionally convey “you are welcome here.”

We have a tradition we are stewarding. A tradition is a mystical thing, a reverberating ritual carrying meaning that grows through repetition. We respect that a ritual – especially one whose meaning is partly a delicate multilayered joke – loses some power when changed, like a transferred plant cutting. It takes years to grow roots again.

We have a history that is important — it serves as the foundation on which we build. We are aware that the work of writers who are not part of the dominant culture is all too often erased and suppressed. Through the Award, we support the past works that serve as our foundation — and the new voices that point the way to the future.

We care so much about the continued presence of an award celebrating genre work that expands and explores gender. And we care about that award valuing – in its name, in its processes, in what work it celebrates – playfulness, flexibility, adaptability, the brashness of anyone who creates art and the humility of anyone open to reading challenging art, and affection. We can retain the spirit of the Award, preserve its playful incisiveness, through a name change.

We are optimistic about new jokes. And we are optimistic about bridging the traditions we’re keeping (tiara, auction, jury, Honor List, free and open nominations, WisCon, a speech and a choral filk, bakesale, original art, Fellowships to encourage and recognize emerging creators) with broader hospitality and welcome – salt and new bread – for a constituency we cherish.

So… the name?

In deciding on a new name for the former Tiptree Award, there were a few things we tried to bear in mind:

- We were in agreement with the prevailing opinion that awards should not be named after people, no matter how wonderful those people might be.

- We thought it wise to avoid overt textual references as well, for similar reasons.

- We wanted to capture what excites us about the works and writers that the Tiptree Award has honored – which is never the same from year to year and jury to jury.

- We wanted to love the new name, and we want you to love it too.

We think we’ve found a name that meets all these criteria. We hope you will agree. And we’d like to introduce you to:

The Otherwise Award

Isn’t the possibility of imagining, thinking, dreaming, living otherwise what draws us to the genre we love – whether we call it science fiction, fantasy, speculative fiction, magical realism, or something else?

At the heart of the creative work this award has honored for the last 28 years is the act of imagining gender otherwise. We have honored those who expand or explore gender by imagining the world otherwise. Over the next 28 years and more, we expect people’s lived experiences of gender to shift, change, and multiply in ways we can’t possibly imagine. But whatever happens, writers and artists will make sense of it, and push at the limits, by imagining otherwise.

Otherwise means finding different directions to move in—toward newly possible places, by means of emergent and multiple pathways and methods. It is a moving target, since to imagine otherwise is to divert from the ways of a norm that is itself always changing.

With the addition of a space, the name also means “other, wise”: that is, wise to the experience of being the other. Such wisdom might come from direct experience or from careful, collaborative consultation.

The Black queer studies scholar and creative writer Ashon Crawley has a beautiful essay “Otherwise, Ferguson” that speaks to the possibility of otherwise politics:

To begin with the otherwise as word, as concept, is to presume that whatever we have is not all that is possible. Otherwise. It is a concept of internal difference, internal multiplicity. The otherwise is the disbelief in what is current and a movement towards, and an affirmation of, imagining other modes of social organization, other ways for us to be with each other. Otherwise as plentitude. Otherwise is the enunciation and concept of irreducible possibility, irreducible capacity, to create change, to be something else, to explore, to imagine, to live fully, freely, vibrantly. Otherwise Ferguson. Otherwise Gaza. Otherwise Detroit. Otherwise Worlds. Otherwise expresses an unrest and discontent, a seeking to conceive dreams that allow us to wake laughing, tears of joy in our eyes, dreams that have us saying, I hope this comes true.

We’ve always sought and found the works that bring all this to mind and heart. We’re excited to name the Award with a word that encapsulates what we feel it stands for.

What is not changing

Beyond the name, the traditions that have grown up around this award are very important to us. These include:

- Open nominations, where anyone can nominate any work (including their own) at any time of the year and at no cost

- Celebrating MANY works, not just one or two per year, and trying to avoid the heartache of competition among them

- Supporting emerging creators with our Fellowship program, where each year’s Fellows help to choose those who will be honored in the following year

- Funding our program activities primarily through communal efforts, like the bakesale and auction, that transparently reflect your support

- Our WisCon rituals of song, tiara, art, and chocolate

- Space Babe

All of these will continue, and we hope that the Otherwise name will inspire new traditions.

What about all the Tiptree winners?

We will consider everyone who has won a Tiptree Award, been named on the Honor or Long List, or awarded a Tiptree Fellowship, to be retroactive Otherwise honorees. Whether you describe your achievement with the Tiptree or Otherwise name – or with both – is up to you.

What happens now?

For the next two weeks, we’re going to hold off on making any permanent changes while we listen to responses from you – just in case there are any compelling reasons not to use Otherwise that we have missed. You can reach us at feedback@otherwiseaward.org if you would like to share your thoughts.

Then, we will start the process of changing our website, our publications, and all the rest. The actual name change will take a while — and we’ll need help from the community to accomplish it. The administrative aspects of the name change involve a lot of practical details, from getting the new domain names and revising the web site to dealing with the IRS, the State of California, and various vendors. But we are committed to making this change, as quickly as we can manage.

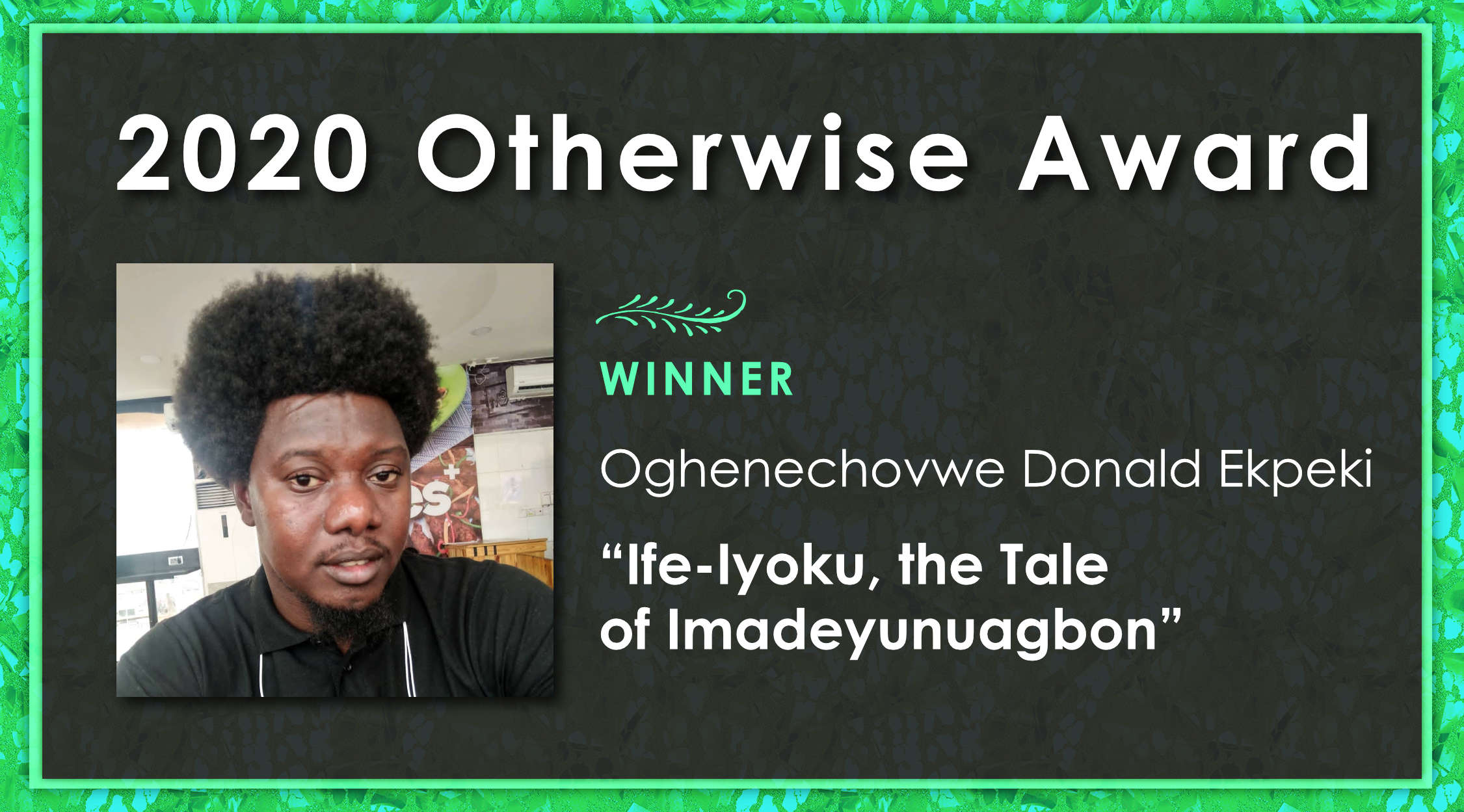

The next round of fellowships (2019) will carry the new name. And at WisCon 44 in May 2020, we will present our 29th award: the first Otherwise Award.

A little help from our friends

Here’s another tradition that will continue: this is an award that exists because of the community that supports it. We can’t do this without you.

Are you excited to join us in imagining Otherwise? Do you have a little time and energy to spare? The Award has always been run by volunteers, and this is a moment where we could really use some help.

We’re taking this opportunity to revisit the way we have administered the Award in the past, to see how we might be able to do things better. We’ll be looking for folks to help us with special projects related to art and design; web and social media; organizational support for the auction at WisCon; and service on the juries that choose the Award and Fellowship winners.

One of the first efforts after the announcement of the Tiptree Award at WisCon was the creation of a cookbook: The Bakery Men Don’t See. Who knows what projects will arise from the Otherwise Award?

If you’d like to help, please email us at info@otherwiseaward.org. (Yes, we’ll be working on changing the addresses.)

There’s a lot to do. Come and help us change the world some more.

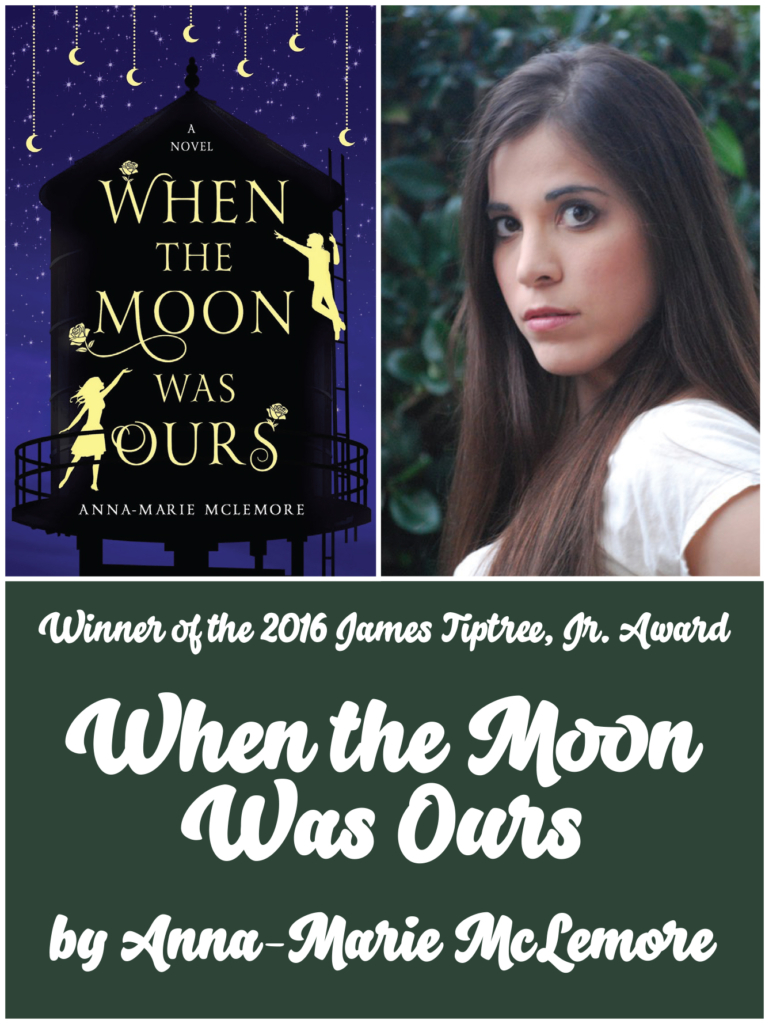

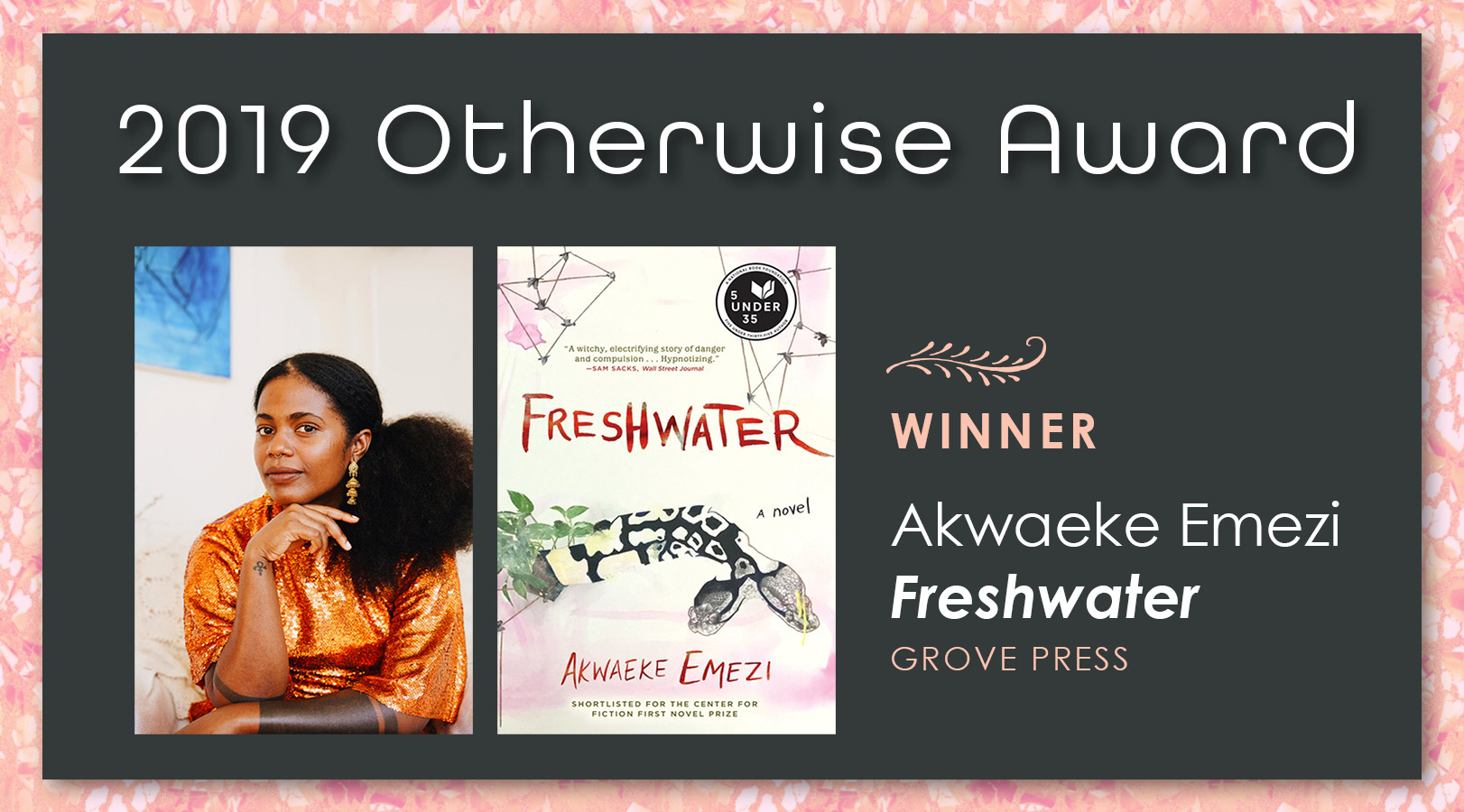

Congratulations to

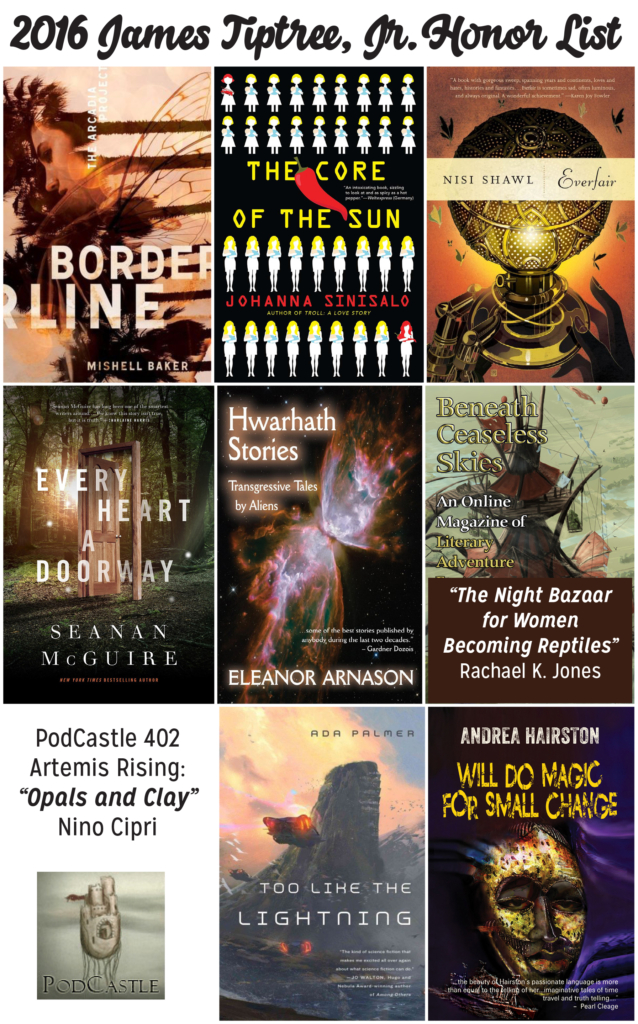

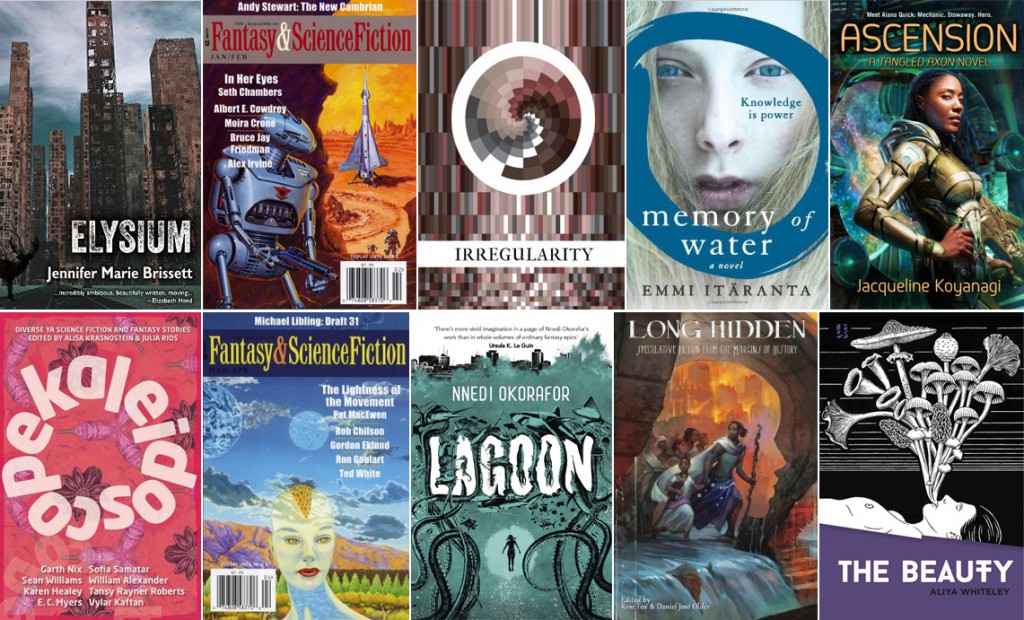

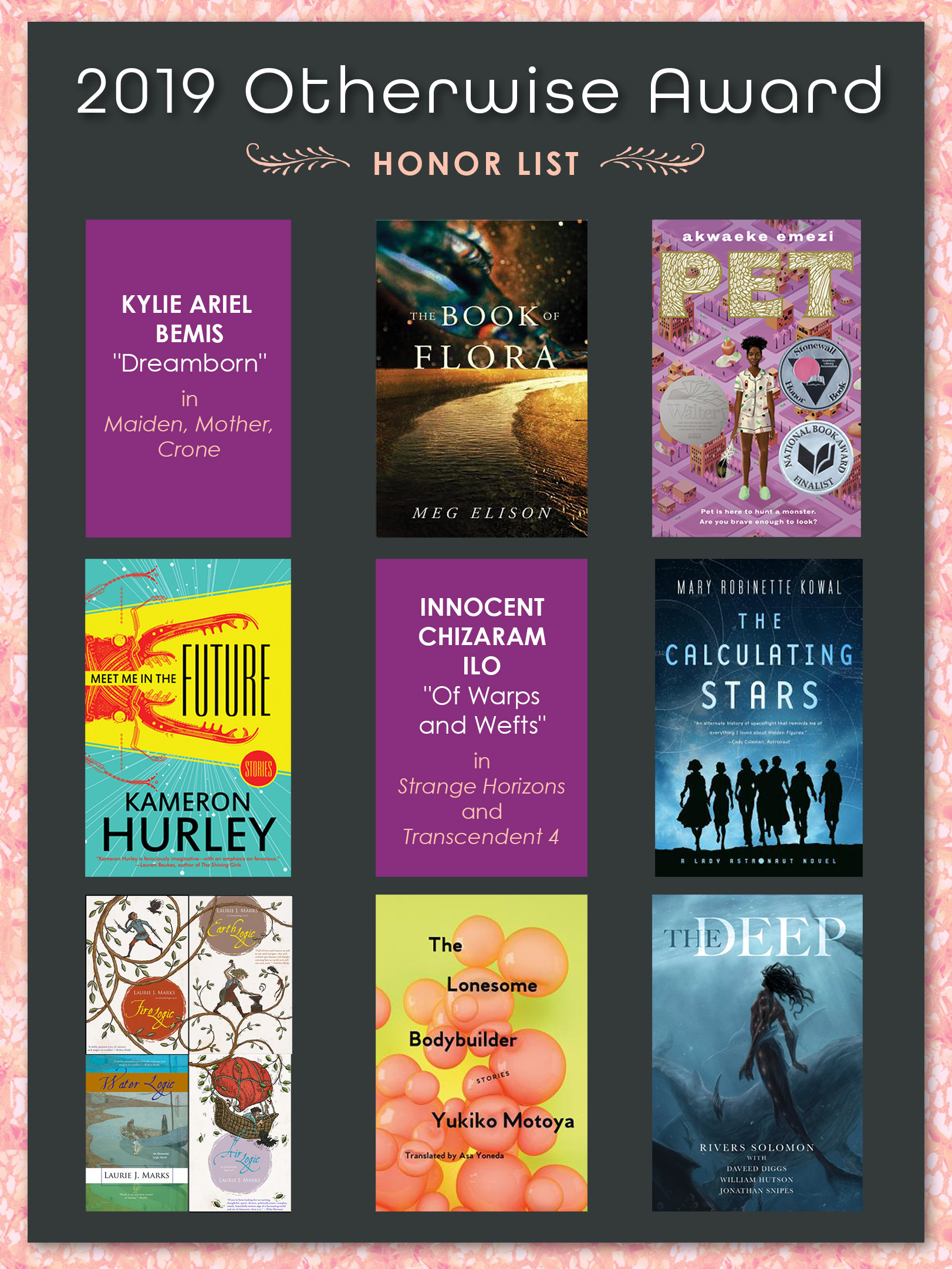

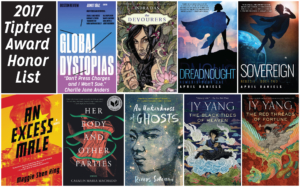

Congratulations to  In addition to selecting the winners, the jury chooses a Tiptree Award Honor List. The Honor List is a strong part of the award’s identity and is used by many readers as a recommended reading list. These notes on each work are excerpted and edited from comments by members of this year’s jury. This year’s Honor List is:

In addition to selecting the winners, the jury chooses a Tiptree Award Honor List. The Honor List is a strong part of the award’s identity and is used by many readers as a recommended reading list. These notes on each work are excerpted and edited from comments by members of this year’s jury. This year’s Honor List is: